Closing the knowing-deciding-doing gap

First things first: surface teachers' mental models

Many of us have heard of the knowing-doing gap (Pfeffer & Sutton, 2000). In education we’ve taken it to mean professional development for teachers that tells them a bunch of stuff but doesn’t affect their practice. In teacher education, we’ve tried to bridge this gap by incorporating things like modelling, rehearsal/practice, action planning and following up on the teacher’s previous action. This focus on behaviour change is incredibly helpful. But there’s still another problem: teachers not using the techniques at the right time for the right reason. We need to solve it to avoid issues like this…

1. Temi is using ‘cold call’ almost every time she wants to know what students understand because she sees it as much better than taking hands up.

2. Robin, leader of teaching and learning, notes that modelling in maths lessons is a real strength. He writes down what the maths teachers are doing so the approach can be shared with all staff who will be expected to do it the same way in their lessons.

Why are these issues?

Well, Temi has found a useful approach but isn’t thinking when it’s appropriate to use it and when it isn’t. Robin isn’t appreciating the factors that go into making an approach work in different contexts.*

To make sure approaches are used at the right time for the right reasons we have to bridge a new gap, the -

Knowing-deciding-doing gap.

We have to support teachers to develop their decision making so they can do the right thing at the right time for the right reason**. How do we develop decision making during coaching? I’ve argued we need to surface and develop teachers’ mental models. Mental models are the cognitive constructs underpinning how we make decisions. But they are unconscious – we don’t often think consciously about them to examine and develop them (Lagnado, 2021). If mental models are tacit, coaching needs to make them explicit so they can be examined and developed.

We can only examine and develop decision making if we can solve these twin problems (Eraut, 2000):

Tacit -> Explicit: find a way to make decision making explicit, and…

Transient -> Captured: capture decision making so it can be examined and developed.

I want to share with you how we can solve these problems so we can examine and improve teacher decision making. This post is about surfacing and capturing. In another post, we’ll look at developing decision making. Early indicators from other coaches are that this approach has benefits - see @catnew’s thread linked at the end.

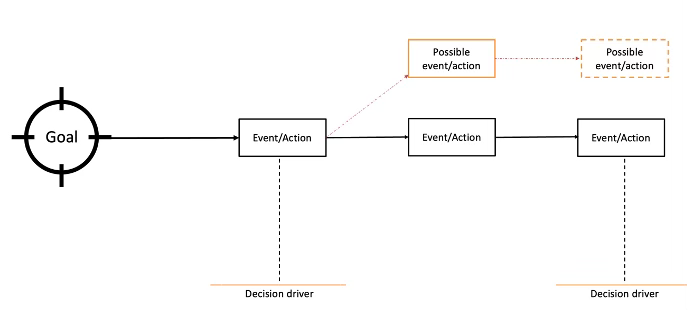

If we want to surface decision making, which we’ve said is underpinned by mental models, we need to understand the components of mental models. These could be mapped like this:

Simply put, we think people’s mental models of situations -

are driven by their goal(s),

include their awareness of the events and actions that took place,

contain their sense of cause-and-effect between events/actions (some causes may be upstream) and

are powered by decision drivers, i.e. reasons for the actions they took.

Better mental models are more sensitive to differences in situations (Dreyfus, 2004; Persky & Robinson, 2017).*** This means they are sensitive to cues that suggest taking a different course of action. For example, a teacher with a better mental model of how to explain a concept may have a default way of doing it and be sensitive to ‘if students appear confused, then try another concrete example’. Their mental model captures more possibilities so the teacher can make effective decisions under various circumstances:

So, when we are trying to surface a teacher’s mental model, we ask questions to uncover these components. Let’s see it in action!

Below is a short clip of Deputy Head and coach, Adam Kohlbeck (@mradamkohlbeck), showing a simple example of surfacing the teacher’s (played by me) mental model. Plus he stops to give commentary on what he’s doing (if you aren’t in the mood for a video, I’ve summarised it below and if you want more, I link to the full webinar at the end of this post):

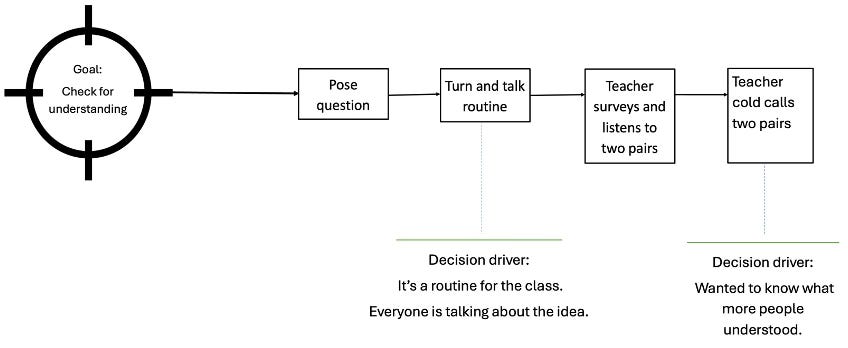

Adam maps the teacher’s decision making like this:

By asking questions directed at surfacing her mental model and then mapping it, Adam can see that he thinks her goal could be more powerful: check everyone’s attention. He also sees a mismatch between her action (turn and talk) powered by the decision driver (it’s a routine for the class…etc) and her goal. Her action powered by that decision driver aren’t going to achieve her goal. The teacher even senses this because she then goes on to use cold call for a few more responses, knowing that turn and talk didn’t do the job of checking for understanding.

You might wonder, why bother surfacing a teacher’s mental model of the situation? Why not just say to the teacher, ‘I think you should be checking everyone’s understanding at this point, so turn and talk wasn’t the best choice. Try using mini-white boards instead.’ This is surely quicker. There are a few reasons why we think beginning by surfacing the teacher’s mental model is important:

1. Assumptions aren’t always right: coaches can assume they know why a teacher did something and what the problem is but without surfacing their current thinking, they might be missing something. This is perhaps especially the case when coaching outside of your subject or dropping in for only a short part of the lesson. For example, there may be subject or student-specific decision drivers the coach doesn’t appreciate until they surface them.

2. Targeting development: surfacing the teacher’s mental model allows the coach to isolate the problem(s) and support the teacher strategically. Sometimes the goal needs work, sometimes the actions don’t match the goal, sometimes the teacher didn’t notice something happen. If we just tell without first surfacing, we won’t know what to develop.

3. Developing decision making: if we want the teacher to do the right thing at the right time for the right reason in the future, they need to think hard about their decision making. Skipping to action may prevent this. Although, we very much subscribe to the view that mental models are also developed through practice and practice under varied circumstances (a subject of future posts) (Banks et al., 2024).

You might be coaching using a model that prompts you to explore a situation where you think the teacher could improve (the ‘probe’ step maybe): this is where we encourage you to start by surfacing the teacher’s current thinking. You might wonder if it takes longer to do this approach. Our experience is that is doesn’t: this is because your aim is much more targeted than a general ‘probe’ - you are trying to surface the components of the teacher’s mental model of the situation, which means you know what questions to ask. If the teacher can’t answer, you can share your interpretation. Having a clear purpose for the conversation keeps it moving.

Let’s look at the types of questions we can use to surface the teacher’s mental model. We need to also be prepared to dig deeper with follow-up questions where the answers we get are too generic and to share our interpretations as coaches too:

Try surfacing mental models yourself using these questions and see what you find. Early indicators are that it works for showing coaches and their coachees where the issues lie: the brilliant @catnew is trying it in her coaching – check out her reflections in her thread.

And for more on coaching…

Listen to the Coaching Unpacked podcast (follow @coachingunpack) where we re-enact coaching conversations we’ve had (with permission): you can hear examples of surfacing and much more.

If you missed our webinar on Cognitive Coaching for Adaptive Expertise, check out the recording!

*Note that there probably are some times where almost complete consistency of approaches across all lessons is beneficial such as with some routines or behaviour techniques.

**I use ‘right’ in a casual sense at the moment since there’s often not just one ‘right’ thing to do. Really I think I mean ‘seemingly most appropriate’ thing.

***Research shows that as expertise grows, people can use their knowledge in a more contextual manner.

References

Banks, B., Sims, S., Curran, J., Meliss, S., Chowdhury, N., Altunbas, H., ... & Instone, I. (2024). Decomposition and recomposition in teacher education (No. 24-08). UCL Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunities.

Dreyfus, S.E. (2004). The five-stage model of adult skill acquisition. Bulletin of science, technology & society, 24(3), pp.177-181.

Eraut, M. (2000). Non‐formal learning and tacit knowledge in professional work. British journal of educational psychology, 70(1), 113-136.

Lagnado, D. A. (2021). Explaining the evidence: How the mind investigates the world. Cambridge University Press.

Persky, A.M. and Robinson, J.D. (2017). Moving from novice to expertise and its implications for instruction. American journal of pharmaceutical education, 81(9), p.6065.

Pfeffer, J. and Sutton, R.I. (2000). The knowing-doing gap: How smart companies turn knowledge into action. Harvard business press.