Ask a teacher with expertise what they’d do in a simple-sounding situation and the answer will always be -

‘It depends’.

They will give you a complex answer taking into account multiple factors that would blow the average person’s mind. Cognitive coaching is about understanding and improving this decision making so teachers learn a repertoire of techniques and use them at the right time for the right reasons.

I think we best understand decision making by thinking about the mental models we use to make them. Thinking about our coaching as developing teachers’ mental models means we come to some pretty important conclusions.

The first is that we all have different mental models of a situation. Mental models are fuelled by our knowledge and no two will be the same. I used to assume that what I saw in a teacher’s lesson would be very similar to what they saw but this might not be the case. This means part of coaching is working out how to align your mental models of situations so you can agree on what happened, what might have caused what, what the teacher’s goal was etc. This is a big insight. It means we can’t just tell a teacher what happened. We have to be curious as to what they noticed and what their interpretation was. Coupled with the fact that mental models are hidden to us, it is important a coach surface both their and their teacher’s mental models of the situation.

Thinking about mental models can help teachers learn meaningfully. Just like a teacher taps into the existing knowledge of their students to connect new ideas, a coach can benefit from understanding the teacher’s current mental model so they can help them develop from there. This also avoids making assumptions about what the teacher was thinking. To do this, we need to ask questions to surface the teacher’s mental models of situations.

Thinking in terms of mental models also gives us direction to our conversations. We can look at the likely components of our mental models: I think these are our goals, events, cause and effect and the concerns that drive our decisions. By understanding the components, coaches know what they are trying to surface and develop: it’s not just about changing actions but also the thinking that leads teachers to them.

All of these reasons and more make it important to surface our mental models and those of our teachers. In this post, we look at how the coach can do this for their mental models. In our next post, we’ll look at how coaches can do this with their teacher’s.

But we have a problem…

Decision making is underpinned by mental models and mental models are invisible lenses even the owner is unconscious of. So how do we make decision-making explicit so we can learn from it and improve? This is a problem leader and coach Chris Passey (@MrChrisPassey) calls our attempt to ‘nail down clouds’…

Nailing down clouds: mapping mental models

We’ve got to understand the teachers’ decision making. This means adopting their viewpoint. But decision-making is hidden and complex. How can a coach capture a teacher’s mental model of a situation? I and a few other coaches are experimenting with mapping mental models. We are hugely indebted to Oliver Caviglioli, author of (amongst other things) the brilliant ‘Organising Ideas’ with the also brilliant David Goodwin, for the idea to map mental models and for support creating the maps.

Map your mental models to prepare for coaching

Here’s a simple example…

I’m a coach and I watch a teacher teach and a situation sticks out to me, so I map what happens.

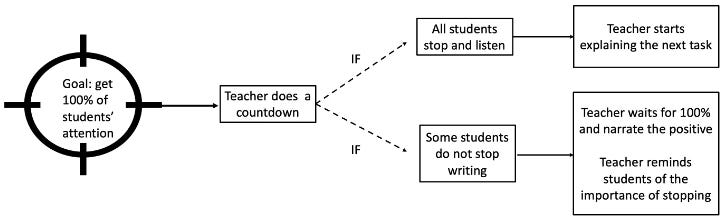

This is my situation mental model. I think the teacher’s goal is to get students’ attention, then I map the actions and events (in boxes) as they lead to one another. The arrows show my sense of cause and effect. There’s no arrow from ‘some students do not stop writing’ because this fact didn’t seem to cause the teacher to do anything different. I’m not sure yet if they noticed.

I then add in what I think is driving this teacher’s decision making. The knowledge that drives mental models and decision making I call ‘concerns’. These are the things I think the teacher was concerned with that drove their decisions:

I think the teacher’s decisions are driven by two competing concerns:

A learning-related concern about the importance of attention and

A curriculum concern about moving on with the lesson to cover content.

Then I decide what I think the problem is in terms of learning:

This is my situation mental model. It’s the situation I think I’ll coach on. It contains my interpretation of what happened and what I think the teacher was thinking. It also summarises the problem I think there is in terms of learning. It gives me a tentative starting point for coaching (but of course I’ll need to ask questions to check if it’s correct).

But to prepare for coaching I don’t just need a sense of the starting point. I benefit from a sense of where the conversation might go as well. What would better decision-making and action look like?

I map out a solution mental model.*

This leads to a natural comparison between the mental models. The solution mental model has a more powerful goal for learning: 100% attention. It has added contingency (if-then), which suggests the teacher does different things depending on two possible circumstances. It suggests that the teacher adopt useful strategies to encourage 100% attention. It’s clear to me how I’d aim for the teacher’s thinking to be different.

But there is a world where the teacher already knows all of these things and just isn’t doing them. Decision making is not just about the techniques teachers have. It’s about the concerns that drive their actions. So, I map out the concerns I think the teacher will need to have to drive better decisions:

In the solution mental model, better decisions are driven by the learning concern about attention. This is fuelling the decisions throughout the situation. I assumed the teacher had a competing curriculum concern around getting through the lesson content. This is a valid concern but it’s possibly misplaced because not all students were paying attention. A better concern for her decision making is around reinforcing routines: routines create the efficiency she is after. This concern can fuel her action to remind students of the importance of stopping.

Through this mapping I can see clearly how I might want to drive the teacher’s thinking to change their mental model and decision making. How I actually do it will depend on what the teacher’s situation mental model really is. I will need to surface this and build from there. More on this and how mapping can help in our next post.

The benefits of mapping

Unlike reams of text, mapping makes thinking explicit without being unmanageable. No map is perfectly accurate. Maps are useful simplifications, like mental models themselves (Parish, n.d). But by making decision making explicit, as a coach I can prepare better for coaching (the subject of this post) and during coaching I can help the teacher understand the difference between their current thinking and potentially better thinking (the subject of the next post).

Mapping also prevents conversations feeling transient. Transience panics us: ‘I can’t hold this all in my head!’. How can we discuss decision making if it’s too much information to hold in our minds? Having the map in front of us with the decisions laid out and agreed gives us the cognitive space to discuss the decision making itself.

Mapping has yet another magic quality. My thinking and my coachee’s thinking is not ‘ours’ in a deeply personal way anymore. It’s out there on the map. We can talk about how to develop ‘the’ mental model underpinning the decision. We work on the artefact together outside of ourselves. This can reduce the tension and emotion around changing our minds or practice.

Mapping is versatile

Coaches can prepare for coaching by mapping at any degree of granularity. If I sense a problem with the teacher’s countdown itself, I could zoom in and map out the steps of the countdown. I can zoom out and map at whole-lesson level. I did this recently when I sensed the teacher’s lesson structure might be contributing to students’ struggling to consolidate ideas. This mapping uncovered a pattern: recurring cycles of the teacher explaining, exemplifying and checking for understanding. It appeared as if independent practice was missing. This, plus some evidence of a lack of recall from students at a few points in the lesson, seemed to paint a picture we couldn’t ignore.

Map and share

Mapping mental models is an art not a science. I’m playing around with it as are some other coaches. We’d love if you tried it too and let us know how it goes.

I’d like to make a free (tentative) guide about how to map mental models. Email me: sarahcottinghatt@cognitive-coaching.org if you’d like this guide or want to contribute to it!

Map your situation and solution mental models and hold them very lightly. They are your tentative plan. How these maps can be used during coaching will be the subject of the next post.

Here’s one of coach and school leader, Adam Kohlberg’s (@mradamkohlbeck), mapping of a situation mental model.

During the observation he wrote his interpretation in purple.

In preparation for coaching he wrote the questions he wanted to ask the teacher in blue.

In the shapes he wrote the teacher’s answers during the conversation.

One map, 2 interpretations + a clear sense of the questions to ask. A meeting of mental models that can now be usefully discussed:

I’m working with schools, individual leaders and coaches to supercharge their coaching. Email me to learn more and get involved sarahcottinghatt@cognitive-coaching.org

For news on a brilliant upcoming coaching podcast and free webinars, follow @coachingunpack on X.

*I may not always have a solution mental model or I may have a few. Coaches don’t always have ‘the answer’ and that’s ok (although they may do). Where coaches don’t have a solution, coaches provide teachers with a helpful lens to heighten awareness of potential problems and support to figure out possible solutions.

References and further reading

Caviglioli, O, & Goodwin, D. (2021). Organise Ideas: Thinking by Hand, Extending the Mind. John Catt.

Crandall, B., Klein, G. A. & Hoffman, R. R. (2006). Working minds: a practitioner’s guide to cognitive task analysis. MIT Press.

Parrish, S. (N.D). ‘Mental Models: The Best Way to Make Intelligent Decisions (~100 Models Explained)’, Farnam Street Blog, [Blog]. Available at https://fs.blog/mental-models/ (30 July 2024).