Read this scenario and tell me what you would do:

You are explaining an important concept to students. Mid way through, you notice a student is whispering to another student. You stop your explanation and say –

“Kiera, silent during my explanation – thank you.”

The student rolls her eyes and puts her head on the desk.

Do you…

Continue your explanation, ignoring this secondary behaviour,

Wait for Kiera to sit up and show that she is listening before continuing,

Continue your explanation for now and address this behaviour with Kiera at a later time?

The correct answer is it depends. Your knowledge of Kiera, of the school’s behaviour policy, of the class dynamic all come into play when making this decision. What about if you’ve just started teaching the class, is your answer different from if you’ve taught them for a while? What if you are covering the class for just this one lesson, would your answer be different then? So much knowledge and experience fuel your decision.

I’ve listened to teachers explain to me what they’d do in this situation and how it would depend on multiple factors. What this tells me is that judging the ‘best’ course of action is seriously complex, even in seemingly simple situations. And this tells me that we really need to dig into this idea of ‘judgement’.

Let's put it really simply:

knowledge/experience -> judgement -> action

I think we are pretty good at helping teachers build knowledge (and teaching is hard – they need a lot of knowledge in at least the domains below, which of course overlap and change):

I think we are also good at helping teachers build a repertoire of teaching techniques: we name them, model them, break them down, recompose them, rehearse and feedback. But I don't think we are good (yet) at supporting teachers to develop their judgement. And this really matters. How can teachers do the right thing at the right time for the right reason (Newell, 2024) if they haven't thought much about their decision making?

It also strikes me that if we skip the 'judgement' part of teaching, we are ignoring the very thing that makes a teacher a professional. So, it’s our duty to think about how coaching improves judgement. But we need to know what judgement is if we are to develop it…

We can better understand judgement if we dig deeper into what is happening cognitively. I think judgement is underpinned by mental models. What’s a mental model?

Mental models are a construct. Put very simply, they are our knowledge of ‘how things work’. They simplify complex situations enabling us to interpret them and act (Rasmussen, 1983). Everyone's mental models are different even about similar, simple things, like trees… Ask a landscaper, a taxonomist and a maintenance worker to categorise trees. Taxonomists categorise based on scientific classifications whereas landscapers and maintenance workers are more pragmatic: landscapers categories reflect the way they interact with trees, i.e. size and appearance; maintenance workers had a category of “weed tree”, reflecting their focus on upkeep (Medin et al., 1997). In other words, we see the world through different mental models depending on our knowledge and experience.

What about teaching? Teachers will see the lesson environment in different ways too (Wolff et al., 2015). More expert teachers will see a lesson and notice the way the teacher set up the class (facing the front listening, working in pairs etc), the nature of the task (to activate prior knowledge, consolidate understanding, for independent practice etc). In other words, they focus on different things and interpret them meaningfully.

A better mental model allows you to -

Magnify important details and interpret them meaningfully

Filter irrelevant ones.

But that’s not all. Mental models also allow us to do some really cool stuff. Because mental models contain causal relationships, they can be simulated, i.e. we can press play and 'run' what might happen if we do something (Klein, 2017). For example, a teacher has mental models related to holding discussions with her year 9 class. She plans to start the discussion with a question about the poem they are studying. Her mental model allows her to quickly simulate the effect of asking the question to the class and she senses that it will be too hard. She decides to break it down and give them some time to write their answers first before discussing. Simulation allowed her to predict the near future and change course to better support student learning.

Just think about it: how much better will a teacher's judgement be if -

they can test the effect of their action in real time?

they can check the things they plan to do and alter them before the lesson?

they can reflect back on their practice and work out what went wrong and what they might do better?

Simulating great mental models allows for this. It’s an expert teacher's superpower.

But with every superpower there’s a downside. Our mental models are tacit (Ford & Sterman, 1998). It’s rare we actually examine our mental models rather than just think with them (Lagnado, 2021). This is why it's so important for coaches to focus their work on helping the teacher surface their mental models, understand them, become dissatisfied with them (when necessary) and change them.

So, what do expert mental models look like?

Better teacher mental models are obviously fuelled by better knowledge. We won't go loads into that here, but teachers need a lot of knowledge (see categories above) and it needs to be well-organised so it’s accessible and transferable to new situations. For example, better knowledge of the curriculum means a teacher’s mental model is more sensitive to subtle errors in students’ answers.

Mental models of experts tend to be fuelled by this better knowledge and sensitive to the particular situation they are in (Dreyfus, 2004; Persky & Robinson, 2017). This situation sensitivity allows the teacher with expertise to size up situations and select appropriate courses of action, i.e. exercise their judgement.

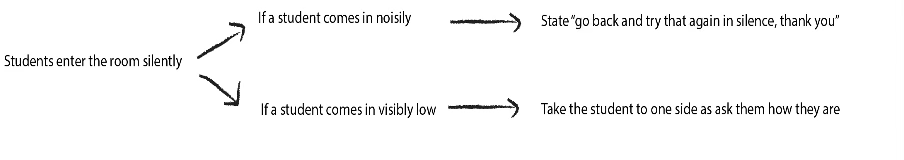

Here's one teacher's mental model of classroom entry:

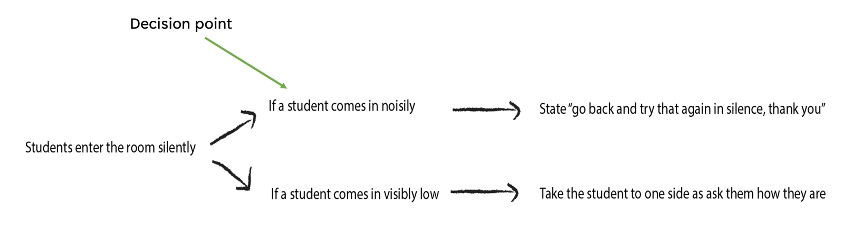

Here's a teacher with more experience and expertise:

Here's a teacher with even greater expertise who knows how to deal with the rogue situations (rare cases):

Expertise is the ability to do the thing that works most of the time and to know when and how to adapt. It’s about recognising ‘decision points’. Decision points are meaningful cues that suggest something different needs to be done.

Recognising and knowing what to do at decision points is part of what it is to have adaptive expertise. More on adaptive expertise in another post.

In short, the belief that teacher judgement should be a big focus of coaching has led me to learn about mental models and how best to develop them. I’ve developed tools for developing mental models that I use when I coach. Future posts will explain these tools and how to use them. Coaching that focuses on mental models I call cognitive coaching, hence the name of this substack.

For more on coaching that changes minds and practice, stay tuned by subscribing.

And…

To join my online course for leaders in charge of teaching and learning in schools starting Jan 2025 (limited to 10 places), email sarah_cottingham@live.co.uk.

References

Dreyfus, S.E. (2004). The five-stage model of adult skill acquisition. Bulletin of science, technology & society, 24(3), pp.177-181; Persky, A.M. and Robinson, J.D. (2017). Moving from novice to expertise and its implications for instruction. American journal of pharmaceutical education, 81(9), p.6065. Both of these papers suggest that as expertise grows, people can use their knowledge in a more contextual manner.

Ford, D.N. and Sterman, J.D., 1998. Expert knowledge elicitation to improve formal and mental models. System Dynamics Review: The Journal of the System Dynamics Society, 14(4), pp.309-340.

Klein, G.A. (2017). Sources of power: How people make decisions. MIT press.

Lagnado, D.A. (2021). Explaining the evidence: How the mind investigates the world. Cambridge University Press.

Medin, D. L., Lynch, E. B., Coley, J. D., & Atran, S. (1997). Categorization and reasoning among tree experts: Do all roads lead to Rome?. Cognitive psychology, 32(1), 49-96.

Rasmussen, J., 1983. Skills, rules, and knowledge; signals, signs, and symbols, and other distinctions in human performance models. IEEE transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics, (3), pp.257-266.

Wolff, C. E., van den Bogert, N., Jarodzka, H., & Boshuizen, H. P. (2015). Keeping an eye on learning: Differences between expert and novice teachers’ representations of classroom management events. Journal of teacher education, 66(1), 68-85.

I love this - such a great way to think about the constant decision making teachers need to do during one lesson. Recognising 'Decision Points' and knowing how to adapt in these moments is so interesting and SO hard to coach around. I also love the notion of adaptive expertise and developing teachers' ability to interpret the important details and filter the irrelevant ones... Developing more expert mental models is such a powerful idea - thanks for the inspiration!

Great post Sarah, thank you