Why do some teachers instinctively know which student to redirect with a glance and which one needs a quiet word at the door?

Why can one teacher spot a lesson unravelling before it does while another only notices once it’s gone off track?

And how is it that long-standing colleagues seems to predict, pretty accurately, how a new behaviour policy will land before anyone has even trialled it?

These aren’t just signs of experience or intuition. They’re clues that something deeper is at work: a construct called a mental model.

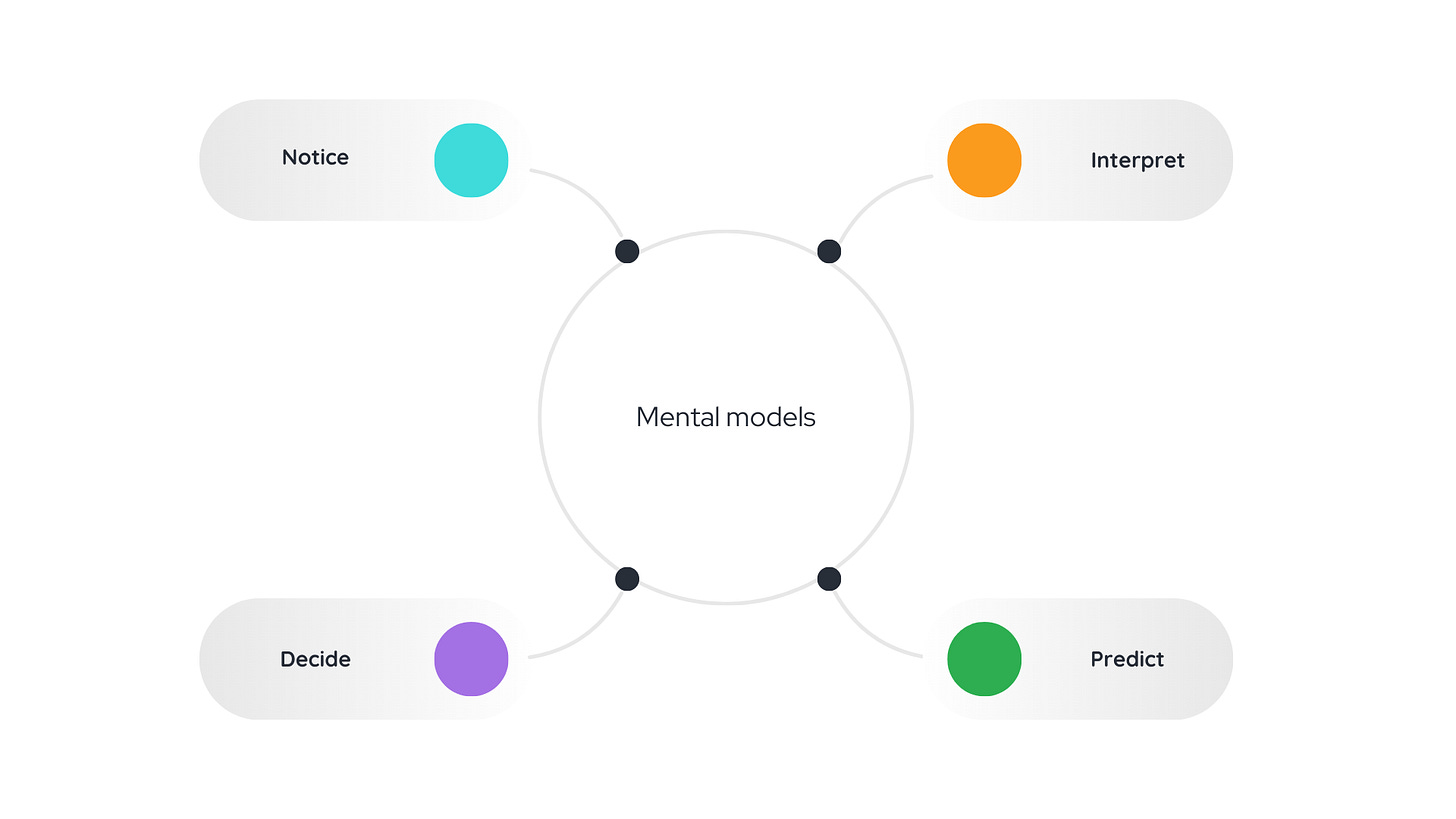

Teachers operate in complex environments, full of moving parts. [1] There isn’t time to process every detail. So, like everyone else navigating complexity, they rely on simplified versions of reality. Mental models are the simplified way each of us thinks a system or situation works.[2] They are our internal maps[3] that help us notice, interpret, predict and decide what to do.

In this post, we’ll look at five key ideas to help you get clearer on what mental models are, how they work in teaching, and how they can be developed.

But first though, let’s look at the variety of situations/systems we have mental models for. Here’s one that might feel familiar –mental models of our schools:

You join a new school, and you show up for your first day. You’re feeling nervous: where are the toilets? How do I print? What are the times of the school day? You don’t really understand how things work around here.

Sensibly, your head of department buddies you up with a colleague who has been at the school several years – Emma. She seems to know everything: which printer works, which students should not sit next to each other, who to go to for your various challenges… Emma knows how things work. She is the colleague who, when a new leader suggests a change, can reply with, ‘We tried that a few years ago. It didn’t work because…’ In other words, she has a great mental model of the school system.

We can see from this example that mental models can (if they are good) help us understand situations and systems. This is because they are built from cause-and-effect associations. These allow us to reason things such as –

“If this happens, then this is likely/less likely to.”

Or as Emma can do –

“If the leader makes this change, it’s likely to go the same way as it did before.”

Keep in mind these cause-and-effect associations – they become important later.

Let’s look at other concrete examples of things we may have mental models about:

The supermarket

Crossing a road

Our relationship with a friend

A car engine

Entry of students into my classroom

Explaining what rivers are to my class

You can see mental models are about all sorts of things: places, relationships, situations, etc.

Now we have a sense of what mental models are, let’s look more deeply at five key things about them…

1: Mental models dictate what we notice and interpret

Like the lenses in those funny glasses the optician makes you wear, mental models blur some things and sharpen others.[4] What gets blurred and sharpened depends on the quality of our mental models (e.g. our goals in a situation and our relevant knowledge).

Compare these two teachers:

During whole-class questioning, a novice teacher’s mental model sharpens their focus on how many students put their hands up and how enthusiastic they are. It blurs the actual answers the students give. The discussion feels lively, but the teacher isn’t checking the students’ understanding.

A teacher with greater expertise has a sharpened lens. They focus on who answers, how, and what it reveals. As they cold call, they probe, and listen for misconceptions. The discussion feels calmer, more directed, and the picture of student understanding is much clearer.

In short, teachers with better mental models literally notice different things.[5] Their mental models focus them on more relevant information for their instructional decisions and help them interpret this information more meaningfully.[6]

What might seem strange, is that evidence suggests those with weak mental models ‘see’ more.[7] But this barrage of surface-level information isn’t helpful. In fact, it’s paralysing. We need good filters to simplify reality if we are to achieve powerful goals like supporting student learning.

The simple takeaway is that are our mental models are the lenses through which we see the world and therefore they are incredibly powerful. Better mental models help us notice less yet interpret cues more meaningfully.

What does this mean for you? It means that when you talk about a teacher having a strong mental model or needing to develop their mental model, you are in part talking about their ability to notice and interpret important cues.

2: Mental models help us predict and decide

Mental models affect more than what we notice and interpret though. They can also help us predict and play out what might happen, or why something might have happened, so we can reason and learn from situations.

To understand how they do this, we need to know something important: mental models contain causal relationships.[8] This allows us to reason things like –

“They’ve moved the bread from aisle 7 where it usually is. Where will it be now? It won’t be near the front of the supermarket as that’s where the chilled aisles are. It must be nearby...”

Or more simply -

“If I step out into the road too soon, I’ll get hit by the car.”

“If I say that to my son, he’ll react badly.”

Just think about how useful this is. We have the capacity to make (and we do make) lots of predictions a day based on our mental models.

Now think what mental models must be like in order for us to reason like this. These cause-and-effect relationships must be dynamic so we can press play on situations and see what might happen. This is called mental simulation.[9]

It allows a teacher to think this during lessons:

“If I ask Bryony this question, she’ll probably struggle to answer.”

“They seem really energetic today as they line up, I’ll speak slowly and calmly to lower the tempo.”

Or this when planning lessons:

“That activity is way too hard for my class. I’ll need to put in some scaffolds…”

Or this when working with a coach to reflect on the lesson:

“If I had moved towards the student, they may have gotten the silent signal that they needed to pay attention, and I would have been able to continue teaching uninterrupted. I’ll try that next time.”

You can see immediately how helpful this simulation superpower is for helping us make better decisions. Accurately predicting into the near future allows us to change course if necessary. This is particularly important in teaching, which is complex and changeable. Indeed, even seemingly routine aspects of teaching require some adaptation.[10] This ability to use great mental models to predict accurately may be why more expert teachers tend to act more pre-emptively than novices.[11]

In short, mental models contain dynamic causal relationships that help us predict and decide what to do. This helps teachers in three ways: in the moment, when planning lessons, and to learn from experiences after the fact.

What does this mean for you? It means that when you say you want teachers to have strong mental models, you are in part talking about their ability to predict and make better decisions.

3: The best mental models are situation sensitive

Better mental models are informed by strong knowledge and accurate cause-and-effect associations to guide decisions in the specific context. Better mental models can therefore be summed up as situation-sensitive.[12]

Teachers don’t develop these mental models overnight. They need a lot of experience and training to do the right thing at the right time for the right reasons.

Here's a concrete comparison of mental models to highlight situation-sensitivity.

Jake has learned that think–pair–share helps students rehearse their thinking before sharing with the class. He sees it as a reliable, all-purpose strategy for encouraging participation and uses it frequently, often by default. Jake’s mental model is built around the general benefit of the technique, but it doesn’t flex much based on the situation. He’s not sensitive to important cues that might suggest a different approach is better for supporting student learning. It’s quite simple cause-and-effect for Jake:

Aliya on the other hand, has a more developed, situation-sensitive mental model. She doesn’t just know that think–pair–share can work; she knows why, when, and under what conditions it’s most effective. She constantly draws on this understanding to match the tool to the context and goal. Aliya’s mental model allows her to notice important cues and act appropriately. Here cause-and-effect associations are more complex:

Both teachers are planning lessons on metaphor. Jake plans to open with “What’s a metaphor?” followed by think–pair–share, assuming it will get students engaged and talking.

But Aliya thinks differently. Her mental model is driven by a better goal: developing a deep understanding of metaphor (not simply getting students talking). She takes into account more important information than Jake: “If I ask them to discuss metaphors straight away, they’ll probably discuss vague definitions because they are unlikely to have the knowledge yet. Think–pair–share works when students have something concrete to build on. I need to give them good examples first.” Aliya focuses on important information relevant to her decision.

Jake, by contrast, treats the technique as good in general, rather than asking, “Is this the right technique for this situation?”

And this ability to do the right thing at the right time for the right reasons really counts in teaching because the complex nature of their task requires teachers to be highly adaptable.

What does this mean for you? It means that your goal is to develop, or support other teachers to develop, situation-sensitive mental models, treating techniques as tools for purposes not blunt instruments.

4: Develop situation-sensitive mental models

So now we know the aim is situation-sensitive mental models that help teachers to better notice, interpret, predict and decide. How do we go about accelerating the development of our mental models or the mental models of those we train?

This is the focus of an upcoming book with Dr Haili Hughes and Adam Kohlbeck, Coaching for Adaptive Expertise. Spoiler: we think adaptive expertise is essentially underpinned by these situation-sensitive mental models and we’ve codified coaching techniques you can use to develop them.

There isn’t the space to detail it here but broadly speaking, we think we need to train teachers in four interlinked areas set out in our Adaptive Expertise Framework:

Here’s each part of the framework in brief:

Understand: mental models are informed by knowledge (see the 5th point below). This knowledge needs to be based on the best available evidence about how students learn. Make sure teachers have access to this knowledge and develop a shared mental model about how learning happens.

Do: use mechanisms to ensure teachers develop a repertoire of techniques. They should be able to execute them efficiently and understand their purpose. They’ll need to see models, break these down to analyse them, and do plenty of rehearsal to learn these.

Decide: to develop decision-making, uncover the teacher’s current mental model of the situation – this is important as our mental models are often tacit (hidden even from the owner!). Once we have the teacher’s starting point, we can help them have insights into issues with their decision-making and develop their mental models to better support student learning. This happens through conversation, representation of their mental model, modelling and rehearsal.

Improve: teachers need to be ‘let in’ on the secrets of how to improve their practice. This involves understanding how to change their behaviour even though behaviour change is hard. They need to be supported to use mechanisms of behaviour change such as context-specific repetition even when no one is there to hold them accountable. It also means supporting teachers to understand how to improve their mental models by testing out new strategies, monitoring their effect and making tweaks if needed.

What does this mean for you? The Adaptive Expertise Framework is a comprehensive way to look at professional development in complex domains like teaching. Paying attention to accelerating development in these four areas using the codified approach we share in the book, we think is key to developing adaptive expertise.

5: Schemas and mental models are probably different

(I’ve put this one last as it may be for the most geeky among us. Feel free to skip to the end if you’re just not that interested!)

You’re probably using the term mental model interchangeably with ‘schema’ (as I used to). Even though what I’m about to say isn’t exactly settled and may not even be that important, I think it’s worth us understanding the potential differences and relationships between these terms. After all, if we’re going to use the terms, we may as well know what we’re talking about.

Before we dig into differences, a couple of similarities. Schema and mental models are both constructs that help explain how humans simplify and represent knowledge so they can deal with the complexity of the world. Also, they are unique for each of us: even if I have a shared understanding of what a car is and a shared mental model of how a car works, it will never be exactly the same as someone else’s.

Contrast 1: Type of knowledge – semantic vs. episodic

Generally speaking, I think we can say that schemas are networks of semantic conceptual knowledge extracted from multiple commonalities across our experiences.[13] For example, we have a schema about supermarkets that contains the general concepts of food, shopping, price, etc. drawn from many encounters with supermarkets. Our schemas contain information about what these things are.[14] They don’t contain episodic details of say, what happened when we last went to the supermarket, i.e. what exactly we bought and who we bumped into. These details have been washed away during a process of consolidation where core parts of memories are replayed to our schemas for storage.[15] Generalised concepts in schemas are easier to access when we need them because they are organised (it is thought) hierarchically, not situation specific, plus bundling up commonalities into concepts makes them economical to think about.

On the other hand, as we have seen, mental models help us make decisions about how to act in situations or they help us reason about a situation or system to work something out. This means mental models are more episodic (event-based) in nature than the semantic concept knowledge in schema. They must be situation specific – built from relevant cause-and-effect relationships in that situation – precisely because they support us to navigate particular situations. Mental models are concerned with function and cause-and-effect.[16] For example, we have mental models related to supermarkets: we know how supermarkets ‘work’, i.e. we pick a trolley or a basket, make our way through the aisles, try not to get in other people’s way ,etc. Food is located and organised intuitively in sections so we can navigate easily, and we must pay before we leave. Schema tell us what supermarkets are, and mental models tell us how they work.

Still, I have issues with the semantic/episodic divide and it doesn’t work perfectly here either.

Contrast 2: use and updating

The second contrast concerns how schemas and mental models are used and updated. Mental models are manipulable structures held in working memory to help us reason. They contain dynamic causal relationships we simulate to make predictions. Schemas are more stable, changing slowly through (re)consolidation to protect well-learned knowledge.[17] While schemas can support reasoning, they lack the dynamic event-based structure of mental models. In essence, mental models help us reason about situations, while schemas give us conceptual knowledge to draw on.

Their relationship isn’t fully clear, but they likely influence each other. Schemas probably inform mental models, i.e. better knowledge leads to a better understanding of our goals and more informed causal reasoning. For instance, knowing how students learn helps us set goals like gaining attention before speaking or linking new content to prior knowledge. Knowing how a curriculum is sequenced informs causal thinking like “If they know X, I can build on it to teach Y.” Learning new conceptual knowledge (e.g. about dual coding) may reshape our schema, which in turn updates our mental model of lesson design and attention.

Likewise mental models probably enrich schema. A failed strategy (e.g. a public correction upsetting a student) can update our mental model of that situation, which over time may alter our schema of that student. Or repeated experiences of group work falling flat may refine our mental model of cause-and-effect (essentially why it’s not working) prompting a shift from a very general schema about group work: “group work is engaging” to a more nuance one: “group work works when roles and accountability are clear.”

Credit: Oliver Caviglioli

Finally, there’s debate about where mental models “live.” Schemas are clearly in long-term memory, but mental models seem to operate in working memory – built on the fly to reason through situations. [18] However, elements of them may be stored in long-term memory too. [19] Are these hybrid schema-mental models or ‘action schema’? Do we ever hold full models, or just construct partial ones from memory? I’m unclear. [20]

To sum up…

1: Mental models affect what we notice and interpret in situations.

2: Mental models can support our predictions and decisions.

3: Better mental models are situation-sensitive, helping us make especially good decisions in the situations where context really matters (like teaching).

4: Developing situation-sensitive mental models involves developing competence in four areas – understand, do, decide and improve.

5: Mental models and schemas are different and probably affect each other.

If you would like to talk more about developing decision-making, get in touch! sarahcottinghatt@outlook.com!

For more on decision-making follow and read publications by key researchers in the field of Naturalistic Decision Making including -

Brian Moon: https://www.linkedin.com/in/brianmoonperigean

Gary Klein: https://www.gary-klein.com/

[1] Sabers, D. S., Cushing, K. S., & Berliner, D. C. (1991). Differences among teachers in a task characterized by simultaneity, multidimensional, and immediacy. American educational research journal, 28(1), 63-88.

[2] Sieck, W.R., Klein, G., Peluso, D.A., Smith, J.L., Harris-Thompson, D. and Gade, P.A., 2007. FOCUS: A model of sensemaking. Fairborn, OH: Klein Associates.

[3] Parrish, S. (N.D). ‘Mental Models: The Best Way to Make Intelligent Decisions (~100 Models Explained)’, Farnam Street Blog, [Blog]. Available at https://fs.blog/mental-models/ (30 July 2024).

[4] Ford, D.N. and Sterman, J.D., 1998. Expert knowledge elicitation to improve formal and mental models. System Dynamics Review: The Journal of the System Dynamics Society, 14(4), pp.309-340; Jones, N.A., Ross, H., Lynam, T., Perez, P. and Leitch, A., 2011. Mental models: an interdisciplinary synthesis of theory and methods. Ecology and society, 16(1).

[5] Berliner, D.C., 1988. The development of expertise in pedagogy. AACTE Publications, One Dupont Circle, Suite 610, Washington, DC 20036-2412.

[6] Berliner, D. C, 1987. Ways of thinking about students and classrooms by more and less experienced teachers. In Calderhead, J., 1987. Exploring Teacher’s Thinking. Cassell Education.

[7] Wolff, C.E., Jarodzka, H. and Boshuizen, H.P., 2021. Classroom management scripts: A theoretical model contrasting expert and novice teachers’ knowledge and awareness of classroom events. Educational psychology review, 33(1), pp.131-148.

[8] Khemlani, S.S., Barbey, A.K. and Johnson-Laird, P.N., 2014. Causal reasoning with mental models. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 8, p.849.

[9] Klein, G.A., 2017. Sources of power: How people make decisions. MIT press.

[10] Hu, Y., 2024. Reconceptualizing Teacher Adaptability: the Teacher Adaptive-Cognition Theory (Doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University).

[11] Berliner, D.C., 2004. Expert teachers: Their characteristics, development and accomplishments. Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society, 24(3), pp.200-212.

[12] Hu, Y., 2024. Reconceptualizing Teacher Adaptability: the Teacher Adaptive-Cognition Theory (Doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University).

[13] Ghosh, V. E., & Gilboa, A. 2014. What is a memory schema? A historical perspective on current neuroscience literature. Neuropsychologia, 53, 104-114.

[14] Pontis, S., & Babwahsingh, M. 2023. Information Design Unbound: Key Concepts and Skills for Making Sense in a Changing World. Bloomsbury Publishing.

[15] Squire, L. R., Genzel, L., Wixted, J. T., & Morris, R. G. 2015. Memory consolidation. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 7(8), a021766. These details can still be accessed with specific external or internal cues but these memories aren’t thought to be part of schema.

[16] Pontis, S., & Babwahsingh, M. 2023. Information Design Unbound: Key Concepts and Skills for Making Sense in a Changing World. Bloomsbury Publishing.

[17] McClelland, J. L. 2013. Incorporating rapid neocortical learning of new schema-consistent information into complementary learning systems theory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(4), 1190.

[18] Johnson-Laird, P. N. 1983. Mental models. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

[19] Nersessian, N. J. 2002. The cognitive basis of model-based reasoning in science. Pages 133-153 in P. Carruthers, S. Stich, and M. Siegal, editors. The cognitive basis of science. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

[20] I have to remind myself at times like this that we are talking about constructs (mental models and schema) within constructs (working memory and long-term memory) and climb out of the rabbit hole.

This looks familiar 😊. Great further comments / q’s at the end. For the purposes of education, I don’t think it matters. But re the rabbit hole, that’s still pretty deep. The concept of ‘long term working memory’ is used to model AI (meaning LLMs) on our mental model formation, but it’s still an imperfect science - because our cognition and computer’s use fundamentally different soft/hardware.

You could show the mental model and schema circles in Oli’s diagram overlapping, but it’s best to leave it as is I think for simplification 👍. Hope you’re well!

Looking forward to the book Sarah, the framework will be e useful coaching tool